I Grew Up by the 'Jaws' Location. Never Saw a Shark, But Now...Wow!

'Shark, Shark, Shark! Get People Out of the Water!'

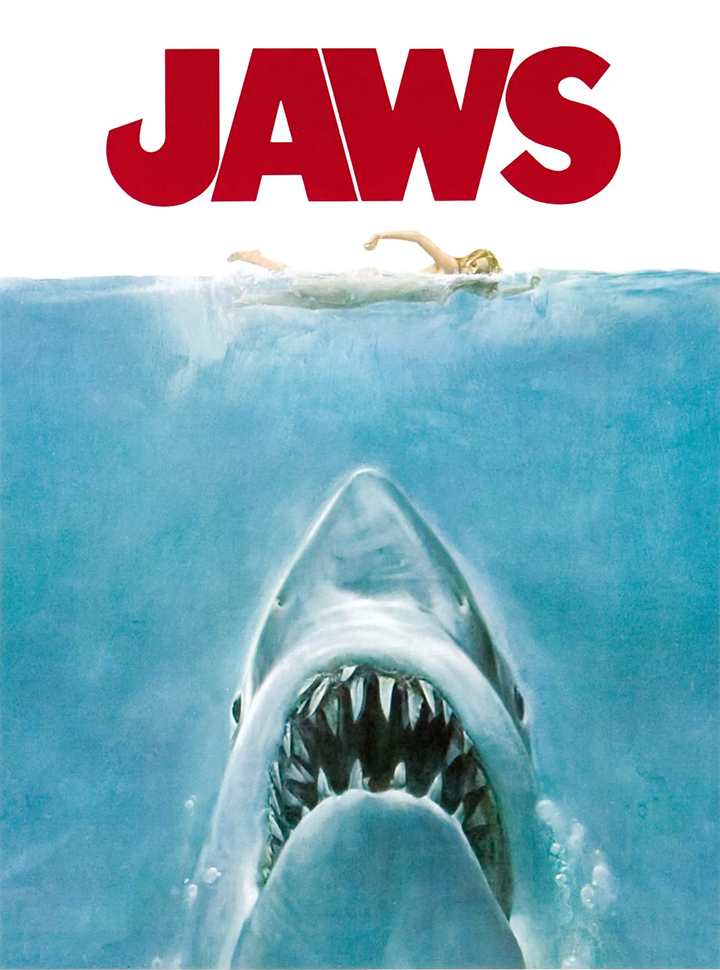

The 50th anniversary of the movie Jaws is being widely commemorated because of the film’s cinematic, cultural and social influence. It is being marked by television specials and multiple events around where the movie was filmed, which is also where the fictional events were to have happened.

I was 20 when “Jaws” came to the Buzzards Bay Theater in 1975. My hometown of Wareham was just around the corner from the island of Martha’s Vineyard where Jaws was filmed.1 I had spent the past dozen years swimming in local waters and sailing our Cape Dory sailboats2—almost daily all summer long.

Wareham has more miles of beachfront than any other town in Massachusetts—54 miles compared to about 125 for the entire island of Marthas Vineyard.

I never, ever saw a single shark off any beach. Not a single shark while underway on Buzzards Bay or Cape Cod Bay. I never saw a shark when I sailed to “the Vineyard.” I never heard talk about anyone seeing one either.

The closest thing were the dogfish we’d catch while fishing offshore for cod. When we were stupid enough not to throw them overboard, the darn things would give birth to live little sharks as they lay dying in the cockpit of a cabin cruiser. 3

Point being: Jaws may have been a scary monster movie, but it was as remote as Godzilla from actual experience in our corner of New England. Sharks were not a thing back then, but the movie took a psychological toll nonetheless.

My uncle Jack Carlson had been an early adopter of SCUBA diving during the 1950s and 60s, when they were still developing the technology we use today. Uncle Jack was good at it. He got regular calls from police asking him to retrieve the corpses of folks who had fallen through pond ice and drowned.

He also had a recreational license to dive for lobster in Massachusetts waters. At some point, he did a 90-foot free-dive at a drop-off near Provincetown after reading about Polynesian pearl divers doing so.

Jack was as lean and fit as ever when I asked him how the diving was going. “I quit,” he said. “Ever since Jaws, I couldn’t enjoy it anymore.”

A great white shark was swimming inside Jack’s brain—dun-dun, dun-dun—even though the animals themselves were absent. Galeophobia is the clinical term for a fear of sharks, and my uncle was exhibiting the symptoms.

Origins

The Jaws story, as written in the Peter Benchley novel, had its origins in a series of 1916 shark attacks in New Jersey and a real-life shark-murdering guy named Frank Mundus who fished out of Montauk on Long Island. Mundus is widely believed to have inspired the Quint character in the novel and movie.

Four swimmers were killed and another critically hurt in the Jersey Shore attacks, though it is just as likely that a bull shark was responsible, not a great white.4

Food Source

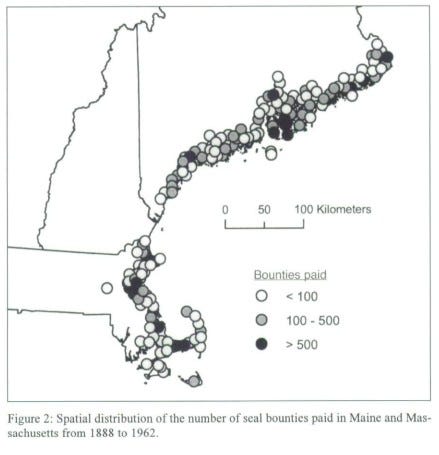

Just 18 years before the New Jersey attacks, Massachusetts and Maine had begun encouraging the killing of seals, through a bounty system. Fishermen argued that seals were stealing their livelihood, which was true in a way. Lobstermen were even convinced that seals were opening their traps to eat the bait and catch.

The solution was a shotgun loaded with deer slugs. At town hall, you could trade a sliced-off seal snout for ten bucks. (By comparison, crows’ feet only got you a nickle.)

According to researchers, 135,000 harbor and grey seals had been killed under the bounty system by the end of the 1960s. Then, the federal Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 outlawed seal killing altogether. The seals gradually repopulated.

By the 1990s I was using a long lens and a tripod to try to get photos for my newspaper showing small seal colonies sunning themselves on rocks at the mouth of the Merrimack River.

The mechanical great white in Jaws was all alone in 1975 because real sharks stayed away. There were no seals to eat. When the seals did come back—New England now has an estimated 100,000 harbor and grey seals—so did the great whites.

There’s irony in that. Scientists have estimated that there have been up to 800 individual great whites in Cape Cod waters over a recent four-year period.

If the great white shark were as malevolent as Benchley and Jaws diretor Steven Spielberg had portrayed, the species would be chowing down on tourists like they were shrimp in a wedding buffet.

Jaws Moments

In 2018, Massachusetts finally had a couple events right out of the Jaws script. Two great white attacks happened in Cape Cod waters, one of which was fatal. Arthur Medici died while surfing off Wellfleet on the “Outer Cape.”

Writing in a May 14, 2019 story for Boston magazine, writer Casey Sherman described the event in gruesome detail:

Fellow surfers saw a giant eruption of water, followed by the sight of a shark thrashing and whipping its tail back and forth around Medici’s body. Before Rocha could think, his arms and legs began churning furiously toward Medici, closing the distance with each stroke. “Arthur! Come to me, come to me!” he shouted, swallowing and spitting out mouthfuls of bloody saltwater. “You’ll be fine. You’ll be fine.”

Medici did not respond, floating motionless atop a small wave. When Rocha finally reached him, Medici was unconscious with his head face-down in the water. The Everett High student and commander of his school’s junior ROTC class instantly remembered his rescue training, getting behind Medici, placing both hands under Medici’s armpits, and swimming several more yards until his feet touched the sand. Rocha used his remaining strength to drag his friend onto the beach.

“Shark! Shark! Shark!” he gasped. “Get people out of the water!”

Predictably, there were some calls to kill sharks or kill seals, or both, to save Cape Cod’s all-important tourist industry. Calls for “lethal management”5 of sharks has its own sociology term. It’s called the “Jaws Effect.”

In Massachusetts, however, the official response to shark attacks was very un-Jaws-like. Public attitudes toward sharks had evolved quite a bit over the past four decades. Even shark tournaments down in Montauk are catch-and-release now. Lethal shark-fishing contests, which had thrived post-Jaws in the spirit of revenge,6 have come under increasing fire by the ecology-minded and animal-rights crowds.

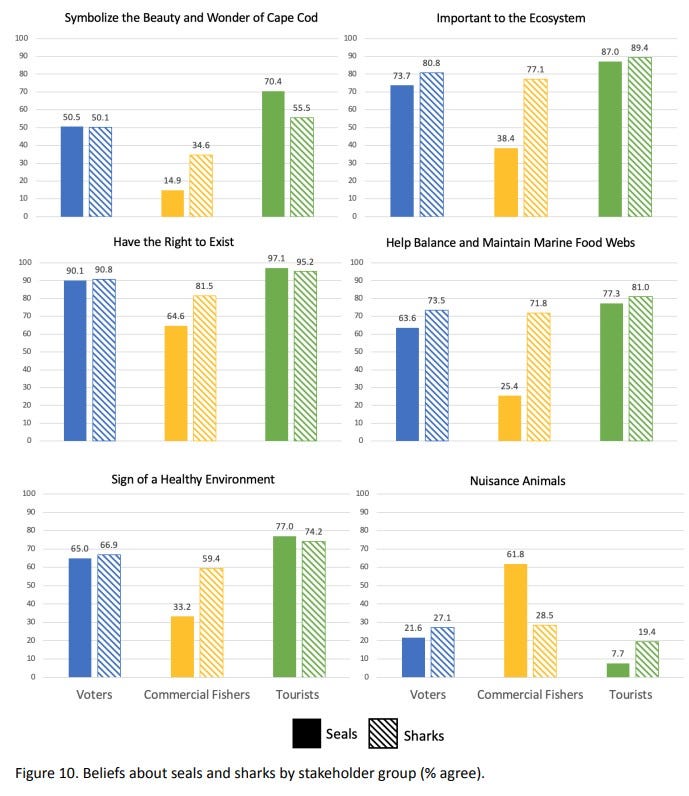

As for killing seals, well, they are just too darned cute. (Unless you fish for a living, then they are not cute at all.)7 Here’s what the 2021 study “Human Dimensions of Rebounding Seal and Shark Populations on Cape Cod” said:

Voters and especially tourists view seals favorably. They hope to see them on Cape Cod. They largely perceive seals as beneficial, positive and enjoyable. They believe that seals are an important part of the marine ecosystem and a sign of a healthy environment. Commercial fishers hold different views and are more negative in their perceptions of seals and their ecological, economic and fishery impacts. Commercial fishers blame seals for reducing and suppressing fish stocks, hurting the economy and creating public safety risks by attracting sharks to the area.

Sharks are scary but also get a pass, according to the study:

While sharks generate fear and are viewed as a threat to people by the majority of voters, tourists and commercial fishers, the perceived benefits of sharks appear to outweigh the risks. Respondents in all three stakeholder groups view sharks as important to the marine ecosystem. By large margins, respondents in all groups agree with the statement, “I am willing to accept some inconvenience and risk in order to have oceans where marine wildlife can thrive.”

Survey Results, Sharks & Seals

Unlike the folks of fictional Amity, hardly anyone nowadays is blaming the shark. Only a small percentage of people in the three groups surveyed said they thought shark bites were intentional. About 90 percent said sharks bite people by accident.

So, instead of recruiting a 2025 version of Quint, Bay State authorities are relying on signage, lifeguard training, beach patrols, shark-alert systems and public education. (For example, don’t hang out in the water with a bunch of seals, no matter how cute they may be.)

What else helps keep casualties down: 46 percent of tourists surveyed said they won’t go in the water. What’s that word again?

Galeophobia. (Dun-dun, dun-dun.)

The movie was filmed in Vineyard Haven, Menemsha, Chilmark and Edgartown, but mostly in Edgartown. So fictional Amity is most likely based on Edgartown.

I’m talking about the earliest Cape Dories, the actual 10 and 12-footers and the 16-foot Handi-Cat, a beefed up version of the traditional Beetle Cat design.

In the 1980s, an industry was established that sent frozen filets of dogfish (aka sand sharks, perhaps incorrectly) over to Britain for fish and chips. But we had no notion of how to make them edible ourselves.

Researchers say warm-water shark species such as bulls are expanding their range northward because of warming ocean temperatures. They are expected to join their great white cousins in New England waters in the near future.

Think “humanely euthanized.” For example, tickling your target to death.

Jaws Director Steven Spielberg, 78, has expressed remorse over Jaws—even though it established his status as a talented director, while he was still in his 20s. “I regret the decimation of the shark population because of the book and film,” he told the BBC in 2022. “I truly and to this day regret that.”

Back in the day, I had always attributed the notion of seals breaking into traps as typical lobsterman bluster, but, sure enough, contemporary accounts and even a YouTube video make the case pretty convincingly.

Hey Peter,

Loved your JAWS piece — made me smile. At Boatshed, “You’re gonna need a bigger boat” is on our shirts, our walls, everywhere. Ironic, of course. Thought you’d appreciate the overlap. Nice work!

Neil

Thanks for covering this, Peter.

I've dived with sharks many times, including diving at places where sharks are fed. I'm opposed to feeding the larger, more aggressive sharks, but I've watched reef sharks and grey nurses zoom in on fish-heads and that's no different from what they do when fishing-boats dump their by-catch. You can learn a lot from watching it up close.

Maybe Australians are used to lethal wildlife, but nationally we've had 186 reported incidents of shark attacks since 1990. Although there are around nine local species that attack unprovoked, only three are associated with fatal attacks here: bull sharks, tiger sharks, and great whites. Together they're responsible for nearly half all attacks, whether fatal or not. The global fatality rate from shark attack is around 16% and that's close to right for Australia too.

Australia has around 2.5 million recreational surfers, but only around 400,000 scuba-divers. Although attacks on surfers see most of the media reporting here, most reported attacks are actually on divers, including divers involved in spearfishing. [https://www.dhmjournal.com/index.php/journals?id=51]

That being so, I'm not even sure what 'accidental bite' means to a shark -- they'll bite opportunistically to see how it tastes and if they like it, they'll bite it some more. Since some species don't put people down after a single bite, we can assume that they're actively trying to eat you. There's some progressive language here toward calling an attack a 'negative encounter', but to me that looks like social management. Do mice have 'negative encounters' with cats, or are they just another prey species to an opportunistic hunter?

Perhaps we have a species blind spot here. We might be an apex predator *on* the water, but splashing around *in* or *under* it, not so much. Maybe that does our heads in.

Regarding the social impact of the movie Jaws in Australia, it resulted in a lot of bigger grey nurse sharks getting spearfished for trophies, and this promoted as a public safety service. And it resulted in adventure boats fishing for great whites just for the thrill of watching them biting. Stupid movie, stupid news media, stupid adventure industry.

But meanwhile, in an alternative reality, off the South Coast of New South Wales is an island called Montague/Barunguba Island where there are juvenile Australian fur-seals being raised by bachelors, there are little penguins in a rookery along with 15 other bird species, and in a trench off the island you can see dozens of grey nurse sharks resting during the day. You can dive or snorkel with any of these critters, and that happens most weekends.

There are vast amounts for ordinary people to learn from watching these animals co-exist and I'm glad that they're all around. We can do much better than reducing our marine understanding to pop sensationalism. [https://www.visitnsw.com/destinations/south-coast/batemans-bay-and-eurobodalla/montague-island]