Houthis Are Using an Off-the-Shelf Simrad Boat Radar; Marines Take the Hint

Halo24 Becomes Tool for Disruption of Global Commerce

Not heard in a group chat: This story was originally published on January 28, 2024. It seems topical today.

Celebrity endorsements are key to selling consumer products, but what if the celebrities themselves aren’t all that likeable? Ask Simrad, which manufactures a marine radar system that just enjoyed a big shout-out, thanks to our villains du jour, the Houthi rebels.

The Houthis are an Arab tribe that is fighting for control of Yemen, a strategic hunk of territory that dominates the Red Sea route to the Suez Canal. Like the Ukranian military, the Houthis are a disciplined, nimble and resourceful force, fighting the Yemeni government and the U.S. equipped and trained forces of Saudi Arabia.

Now, urged on by their sugardaddy Iran, the Houthis are disrupting world shipping traffic through the Red Sea as a way of pressuring the Israelis to back down over Gaza.

What has that got to do with Simrad?

Last week the New York Times published a story about Houthi resilience in the face of U.S. air strikes. The reporters gave a shout-out to a particular piece of gear that is helping to bedevil America and her allies—the Simrad Halo24 dome radar.

The Houthis began buying Halo24s as they brawled with Saudi Arabia through the later half of the last decade. As it has done during the Ukraine war, the U.S. military kept a close watch to learn how Houthis were able to keep the better equipped Saudi forces at bay for half a decade. That’s how the Halo24 came up on the Pentagon’s radar, figuratively speaking

Shoot and Scoot

As Helene Cooper and Eric Schmitt wrote in their Jan. 24 story in the Times:

Lt. Gen. Frank Donovan, now the vice commander of United States Special Operations Command, noticed what the Houthis were doing with the radar back when he was leading a Fifth Fleet amphibious task force operating in the southern Red Sea. Trying to figure out how the Houthis were targeting ships, General Donovan soon realized the Houthis were mounting off-the-shelf radars on vehicles on the shore and moving them around.

He challenged his Second Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion to develop a similar system.

While U.S. air forces are superbly capable of neutralizing super-expensive military-grade targeting stations, they are proving less effective at hitting cheap ($3,099 at West Marine) Halo24-based systems moved around in the beds of pick-up trucks.

Apparently, a Houthi fire team will raise a Halo24 dome on a pole temporarily while they fire a drone or missile and guide it toward a ship. Whether missile or drone, once it hits, misses or gets shot down, the tower is quickly lowered, disasembled and stowed, and the truck makes a getaway—shoot and scoot.

Like the civil war in Yemen, the Simrad Halo24 came into being around 2015, an improvement on the so-called Broadband Radar introduced a few years earlier by Simrad’s then-parent company Navico. Traditional radar uses something called a magnetron to produce repeated bursts or pulses of radio waves. Halo and earlier Broadband radars emit variable frequencies instead of single bursts.

The Corps Recalibrates

Meanwhile, the Marine Corps has been reinventing itself as a force that could engage China asymetrically in a future conflict, using smaller Marine units to “fix” Chinese formations long enough for the U.S. and allies to concentrate forces and join in the fight.

Yep, the Marines adopted both Houthi insurgency tactics and the Halo24, a radar intended for the recreational marine market, most definitely not intended for military use, according to Don Korte, the Simrad product manager in charge of the Halo project.

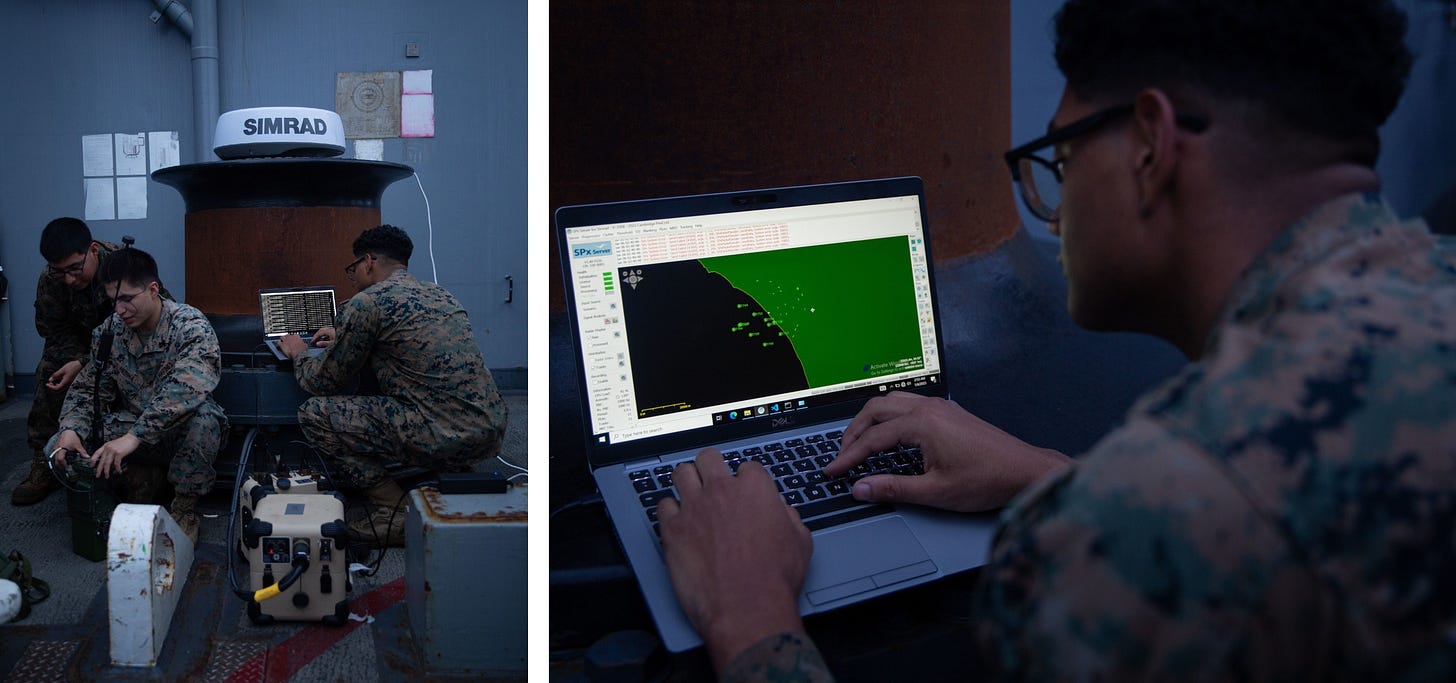

Korte said the radars were designed to work with Simrad’s proprietary multi-function displays, but the Marines have gone another route. One image released by the Marines shows a marine training with the Halo24 using a Dell laptop computer as the interface.

The laptop is in SPx server mode, software developed by the British company Cambridge Pixel, a supplier of radar display, tracking and recording sub-systems. Here’s what the company said in 2017 about its system capabilities as applied to an autonomous surface vehicle or ASV. That is, a seagoing drone

Cambridge Pixel's SPx Server radar tracking software receives radar video from the onboard radars, typically Navico's Simrad 4G or Halo radars. The processing of video to detect targets of interest uses adaptive algorithms to accommodate a wide range of operating conditions. Initially, plots are extracted as detections from the radar that exceed a background level. These plots are then correlated to differentiate clutter from true targets.

Once the target has passed a confidence test, a provisional track becomes established and is subsequently tracked from scan to scan with a multi-hypothesis, multi-model tracker. Navigation data from the ship is used to compensate for own-ship motion. The output from the tracking server is combined with AIS targets, using the SPx fusion software, and the resultant fused track is provided as a standard ASTERIX or TTM message into ASV’s control software.

If you understand any of that, you can probably begin to see how a Halo24 with SPx or a similar software could guide an airborne suicide drone from a Yemeni beach to a passing container ship.

Halo24 has a theoretical max range of 48 miles; actual range depends on both the height of the dome above sea level and the height of the target.

According to Korte, instead of the four- and six-kilowatt magnetrons of traditional pulse radar, Halo uses up to 25 watts of power and a “spread-spectrum X-band transmitter” to send out a signal using what’s called “pulse compression.” The signal burst is comprised of up to six different pulse lengths consisting of a range of frequencies, rather than just one, that upon echo return provide large amounts of data about the distance and direction of targets.

Ben Ellison, founder of Panbo, a website devoted to marine electronics, wrote about Halo’s benefits when Simrad brought the technology to market about eight years ago:

Simrad’s designers understood that short pulses provide good minimum range, but poor long range performance. At the same time—you guessed it—long pulses work well at long range but don’t do so well up close. In layman’s terms, Simrad decided to transmit waves of a variety of frequencies every time, so the system will be effective over its full range, which the company says stretches from 20 feet to 72 nautical miles out (for Halo-6). The idea is that the radar will work just as well in close as far away.

Korte said the Halo radars were also an improvement over the previous Broadband 4G models because their higher power allowed better MARPA tracking of targets. MARPA stands for Mini-Automatic Radar Plotting Aid, and we civilians use it for collision avoidance.

But you can see how it might also assist in vectoring a moving aerial or surface vehicle to its collision with a moving target such as a ship. Halo can track 10 MARPA targets simultaneously, 20 in dual-screen mode, Korte said.

For us, one of the cool functions is the Halo24’s ability to operate displaying dual radar ranges overlaid on dual charts.

“You can do chart-chart with radar on dual range and when you change chart scale, the radar will automatically follow the chart range,” Korte said. “I worked very hard to make that work good.”

Masters of Their Own Domain

For the Marines, the name of the game is “maritime domain awareness,” a key mission under Force Design 2030. The Corps’ blueprint for future war-fighting includes a new “Littoral Regiment” that will “help the fleet and joint force win the reconnaissance and counter-reconnaissance battle within a contested area at the leading edge of a maritime defense.”

Capt. Larry Boyd, a Marine officer involved in a joint exercise with Philipines forces in November 2023, highlighted the use of off-the-shelf sensors such as Simrad Halo24s, which he said allow “for a more seamless interoperability in building the maritime-domain-awareness picture.”

What he said.

The Houthis are not the first bad guys to burnish the good name of a product by purchasing them in mass. The Taliban’s choice of Toyota pick-up trucks—referred to as “technicals”—as a platform for their machine guns and missile launchers is another.

And the idea can be applied not just to products but services. In the war movie Full Metal Jacket the drill sergeant hilariously cites the Texas tower gunman (who killed 12 people) and Lee Harvey Oswald, both Marine veterans, as testament to the quality of the Corps’ marksmanship training. Like the Houthis, their achievements/crimes constituted an endorsement.

At this point, some readers may be thinking, so what? The Houthis are shooting at ships, but they haven’t sunk anything. The allied Navies are blasting Houthi ordinance out of the sky, and the one or two hits or ships haven’t caused much damage.

Alas, that argument is true, but it’s irrelevant truth. The fact that the threat exists at all has caused wholesale re-routing of world shipping. That creates delays and higher costs. Shippers’ insurance goes way up. It has been the cause of one of those supply-chain disruptions that everyone prattles on about.

Brunswick Connection

Simrad is now owned by Brunswick Corp., a $6,62 billion Fortune 500 company that absolutely dominates the market for boats, marine propulsion and boating accessories. Brunswick routinely reports to its stockholders about the potential for “acts of terrorism or civil unrest” to disrupt distribution channels or its supply chain.

Brunswick has six facilities in Europe, a continent that benefits mightily from movement of goods through the Suez. European car factories have actually had to shut down for lack of components coming from the Far East.

The irony is that while Brunswick is profiting from the military application of one of its recreational products, it too may be feeling a bit incovenienced by events in the Red Sea. Further deterioration might find Brunswick in the unique position of being hoist by their own petard, after first having profited from the sale of said petard.1

Yeah, unlikely. I know.

Wikipedia: Hoist by his own petard is a phrase from a speech in William Shakespeare's play Hamlet that has become proverbial. The phrase's meaning is that a bomb-maker is blown ("hoist”) off the ground by his own bomb ("petard"), and indicates an ironic reversal or poetic justice.

[Sidebar: I'm getting so addicted to Loose Cannon.]

{2nd sidebar: I've got a Simrad radar and A/P on my escape pod, FWIW.}

"At this point, some readers may be thinking, so what? The Houthis are shooting at ships, but they haven’t sunk anything. The allied Navies are blasting Houthi ordinance out of the sky, and the one or two hits or ships haven’t caused much damage."

We are losing big time, and in an important way, if we are firing a pair of SM-3 missiles, costing $2 million each, at $20,000 Houthi drones. We don't have an endless stock of them. They are not built in a week. We are running out. Spending $4 million to stop a $20,000 drone is not winning.

And importantly, our destroyers cannot reload these vertical-launch missiles at sea, so when they are gone, the ship has to leave the theater to reload pier side. If we get into a kinetic scrap with Iran, these numbers and facts are going to come back to haunt us.

In light of what just happened in the news regarding “targets,” your post is so very timely. This was very informative. As you stated, I’m thinking the same is true for those geniuses using Signal: hoist by their own petard!