Hear Me Out: Maybe the Bahamas Bosses Don't Really Want Us

Carbon-Credit Billions as the BIG Door Prize

This one counts as opinion, folks.

Older-generation Floridians have a useful, if somewhat vulgar expression, “to show one’s ass.” As in, “Your sister’s new boyfriend really showed his ass at the funeral.” It describes the moment when a person publicly reveals an especially undesirable trait.

This cruising fee increase—and the process by which it was rolled out—constitutes a Bahamas-showing-her-ass moment.

Loose Cannon recently reported on the possibility that the Bahamas can earn itself an astounding payout just by protecting its seagrass beds because these beds “sequester” huge amounts of carbon. One estimate put the sales value of “blue carbon credits,” thus protected, at $50 billion. (Story linked below.)

For the folks running the Bahamas, $50 billion dollars has got to be the BIG door prize.

This is a country where the going rate for political “cooperation” is one or two million bucks. Compared to that, $50 billion is a staggering figure. I am not making those bribe numbers up. One comes from a recent indictment, and the other was referenced in a previous Loose Cannon story about a luxury resort proposed for Sampson Cay.1

For the most part, the foreign boating community reacted to the new fees with indignation, except for those predictable few, sniffing that anyone who couldn’t afford the increases should be disqualified from boat ownership and slink away in shame. However, even among those who could afford the extra cost, many said they felt betrayed.

“Insane fees,” said Bob Lorns, writing recently on Medium.2 “These rates are not just regionally uncompetitive; they are globally unmatched.” Bob Lorns, which I’m convinced is a made-up name, was talking about the original bill, before the government backed off a bit and merely tripled existing fees.

Boycott?

Insane? As I used to tell my reporters, when something doesn’t make sense, there’s a dollar amount hiding somewhere out of sight—or in this case, plain view.

Many of us initially called for a boycott, arguing that our collective economic clout would show Bahamian politicians the error of their ways. Boycott advocates are often the same folks that cram cases of beer into every nook and cranny on their boats—and beef, too, if they’ve got a freezer—just to avoid paying high Bahamian prices. (Be honest. Haven’t you always been engaging in a half-assed boycott?)

Susan Costa is a cruiser from Massachusetts who wrote a free guide to the Bahamas. Costa has estimated that cruisers spend between $800 and $1,200 a week there. For lack of hard numbers I’ve spitballed the annual spending two ways, using 10,000 and 20,000 as the number of small craft visiting the Bahamas in a given year, multiplied by Costa's estimates, and assuming everyone is spending six weeks there.

The low number yields an annual contribution of $48 million; the high one, $120 million. The entire yachting segment, which includes all those superyachts and center-consoles, contributes about $500 million a year. Some individual megayachts will reportedly spend a million bucks in a single season.

Obviously, these calculations are open to dispute, but they probably capture the gist of things. That is, we don’t contribute as much as we think we do. And we do anchor a lot. Lorns’ essay warned the Bahamas government to abandon the new fee schedule, or it would be “chasing boats away.”

What if chasing us away is a feature, not a flaw? What if the goal—chamber-of-commerce types excepted—was to discourage us from going to the Bahamas altogether? Pricing theory is a concept in economics that almost everyone understands. It's really simple: Raise prices and some people will stop buying your product. Taxing the crap out of cigarettes got a lot of smokers to quit.

Occam's razor is another concept that I introduced to my new reporters once upon a time. It’s a problem-solving principle that suggests the simplest explanation is usually the most likely one.

Prime Minister Philip Davis has publicly blamed the cruising community for taking more than its share of fish, polluting Bahamas waters with sewage and messing up the seabed with our anchors. “For years, unregulated anchoring has significantly damaged coral reefs and seagrass beds—critical marine habitats supporting biodiversity and carbon sequestration,” the Davis government said in a recent news release.

Rhetoric such as this suggests the fee hikes were being sold domestically as a way of punishing us. At the very least, they were a raised middle finger, and Davis knows it. So, maybe he and his party would really rather we not visit at all and thus spare their precious carbon-cash seabed from the theoretical ravages of Rocna and Mantus. Only those protests by the Bahamas marine industry, hoteliers and island shopkeepers appeared to have kept this administration in check.

Salivating?

Carbon Management Limited (CML), a Bahamian-controlled public-private partnership, will turn seaweed into carbon-credit cash via “scientific management,” according to a government news release. Soon, CML and the Bahamas government might be able to tell their carbon-credit broker that higher cruising fees had successfully reduced visits by the cruiser cohort prone to anchoring.

If social media posts are any indication, some of us won’t be able to afford a visit because of higher fees, and many who can afford the fees, will refuse to come out of principle.

Either way, Bahamas carbon-credit salespeople might argue, higher fees will be reducing the number of us bottom-scrapers by some percentage. Twenty-five percent would be impressive, don’t you think? Those that do come may find their favorite anchorages filled with moorings, another form of seagrass-meadow protection, supposedly.

What I am saying may be wrong, but it’s not a conspiracy theory. It is a heuristic analysis based on an assumption that Bahamian leadership is salivating at the thought of $50 billion to divvy up. Henceforth, all government policy regarding Bahamas waters should be examined in this context. Whatever ideas might not seem so insane then.

Read the section entitled “The Connected Lawyer.”

Marine Economy—And Bahamians, by Bob Lorns

In an astonishing display of economic short-sightedness, the Bahamian government has introduced what are now the highest yacht cruising and anchoring fees on Earth. As of July 1, 2025, fees will range between $500 (for the smallest of vessels) to $1000 annually for cruising permits, and $3000 to $8000 for Frequent Digital Cruising Cards (FDCC) with a two-year validity — plus anchoring fees that range from $250 to $1,500 per year. And what if you paid for the year, but wanted to leave for a few weeks? Well, if not returning within 30 days of your initial entry, you get to pay for it all over again, doubling the already insane fees!! These rates are not just regionally uncompetitive; they are globally unmatched.

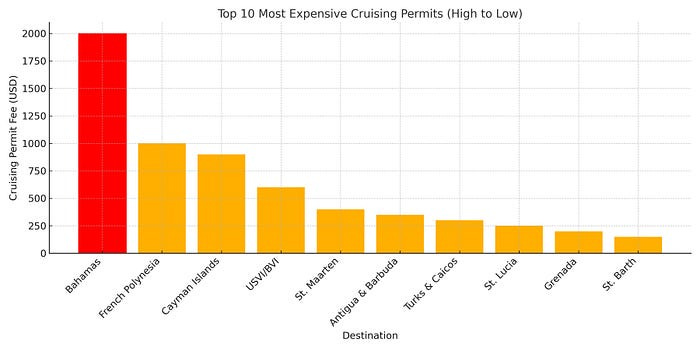

Around the world, popular yachting destinations like Greece, French Polynesia, Australia, and the Caribbean offer cruising permits for a fraction of that cost — usually between $100 and $500 per year. Even destinations with stricter biosecurity or port regulations rarely exceed $600 total for extended visits. In contrast, the Bahamas has chosen to isolate itself at the top of the expense pyramid, pricing out all but the ultra-wealthy.

The result is a textbook case of price elasticity gone wrong. Raising prices too far results in demand collapsing. Yacht owners are famously mobile and budget-conscious, and they are already voting with their sails. Forums, social media groups, and mariner networks are filled with posts from captains and charter operators warning others to avoid Bahamian waters entirely. Some are even rerouting mid-season to avoid what they see as economic exploitation.

But this is not just about luxury tourism or cruising freedom — it is about livelihoods. The Bahamas’ family islands depend on these visitors. Unlike cruise ship passengers, yacht guests stay longer, spend more locally, and support micro-businesses: grocery stores, fuel docks, water taxis, local guides, beach bars, laundry services, mechanics, and markets. Every visiting boat brings value to the communities it touches. Take the boats away, and that value disappears.

This is not hypothetical — it is déjà vu. When the Bahamas last raised VAT and permit fees, visiting yacht numbers dropped sharply. Charter bookings declined, and some foreign-flagged operators pulled out entirely. Now, with these record-breaking fees, the damage will be far worse — and longer lasting.

Government officials may argue that these measures are designed to increase revenue or “protect resources,” but in practice, they represent a massive misunderstanding of basic economic principles. Fewer visitors mean fewer permits sold, fewer taxes collected, and fewer dollars spent across the islands. The nation will not gain revenue — it will lose. And its reputation as a premier yachting destination will suffer in ways that may take decades to repair.

Meanwhile, competitors across the globe are taking advantage of the Bahamas’ misstep. Their leaders are silently laughing at the Bahamas, and salivating as they prepare for the growth in their own GDPs as the Bahamas begins to hemorrhage tourists. From Antigua to Fiji, countries are welcoming cruisers with open arms and affordable entry. They are securing long-term economic benefits and building goodwill while the Bahamas alienates the very people who once kept its out islands alive with activity and income.

The Bahamas still has the beauty, the culture, and the world-renowned cruising grounds. But no amount of turquoise water can outshine a hostile policy. If this continues, the waters of the Bahamas may remain crystal-clear — but increasingly empty.

There is still time to reverse course. The government can lower the fees, streamline clearance procedures, and rebuild trust with the global yachting community. But if they do not, they are not just chasing boats away — they are strangling the throat of their own maritime economy, and in turn, stopping the heart that pumps the economic lifeblood to their own citizens.

Peter, good on you for calling this the way you see it.

“Insane fees,” said Bob Lorns, writing recently on Medium.2 “These rates are not just regionally uncompetitive; they are globally unmatched.”

This is statement by Bob is not true. I can think of several places off the top of my head where fees to visit are much higher. Galapagos Islands, Bonaire, Monaco, Anguilla, The BVI (to some extent due to mooring mandates) etc. I’m sure there are more if I looked.

I do like the way you link the $50B sea grass scam. Perhaps scam is not the correct word but I’m not a big believer in the worth of carbon credits. I can imagine the uproar of some tree huggers when they find out their beloved sea grass for which they have paid to save the world is being destroyed by anchors. This most certainly is an image the Bahamas will wish to avoid. So perhaps there is in fact a desire to minimize the private vessels. If you recall, I had an inkling that the whole mooring things wasn’t gone when the cease and desist came out.

Your estimate of the private yacht industry aligns with what I have been telling cruisers for years. They really do not help the economy very much. Yes, there are a few small businesses who depend on this segment of tourism, but the key word is few. Cruisers are a myopic lot who struggle to see beyond their own footprint.

Susan Costa’s numbers are missing something. How much of what cruisers are spending is actually staying in the Bahamas and creating jobs. We live an above-average lifestyle on our boat and stay in marinas more than most. We also rent cars and travel inland and take tours. Our entire budget, including health insurance, boat insurance etc is about $1,500 per week. What we actually contribute to the local economy is much less. Things like Starlink subscriptions don’t count. Nor does the cost of fuel and groceries – very low profit margin items that add little to the economy.

You said it before. Cruisers are a parsimonious {great word BTW} bunch, myself included. I once watched a couple of cruisers share a can of soda in a bar using the free wi-fi for more than 2 hours while the bar was busy and needed tables for customers wanting to place food orders. I wish I could say this is an isolated incident, but it isn’t.

The main reason French Poly passed such tough anchoring restrictions was due to cruisers stealing water from restaurant facets (much of ours was take by other cruisers in the marina – we had to lock it eventually), leaving bags of trash on the side of the road, doing laundry in restaurant bathrooms (if located outside) and anchoring close to very expensive over the water bungalows. How exactly is this helping local businesses?

Not everybody looks at our boats with dreamy eyes. Sometimes we are just an eyesore on the horizon.

"Bahamian leadership is salivating at the thought of $50 billion to divvy up". Sure they are. And it won't go much past that "leadership" except for their own families. That's been proven in the past in the Bahamas. Some may say the local cruiser community vendors won't suffer if cruisers abandon the Bahamas. Maybe. But it's highly probable they won't enjoy any of that $50 billion windfall either.