Three. Nasty Business, Dreams of Africa

At the end of his life, Ernest Hemingway was judged to be paranoid and delusional because he claimed that the FBI had him under surveillance. Then in 1983, the FBI released a 127-page file it had kept on Hemingway since the 1940s, confirming Hemingway was indeed being watched by agents working for J. Edgar Hoover, who took a personal interest in Hemingway.

Writing for the New York Times 50 years after Hemingway’s death, friend and editor A.E. Hotchner said he believed the FBI's monitoring of the Nobel Prize-winning author over suspicions of links to Cuba "substantially contributed to his anguish and his suicide."

In 2009, authors with access to archives of the Soviet-era spy agency revealed that the KGB had recruited Hemingway as an agent in 1941, though the connection was severed when Hemingway failed to produce any useful intelligence.

As far as the author’s motivation, one might infer a certain insecurity. His spare style of writing was meant to denote an iceberg with the tip above the water implying vast meaning beneath the surface. Did Hemingway doubt his own ability to articulate the motivations of his characters in any meaningful way? Face it, he was no Virginia Woolf. He had yet to write The Old Man in the Sea. At that particular moment of his life, what Hemingway had was surfeit of physical courage and a deep psychological and commercial desire to continue to be relevant.

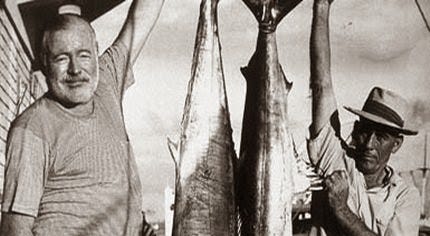

The grist for Papa’s mill would have to come from his beloved notions about action, whether it be spying for the Kremlin, hunting U-Boats or some other nasty business.

1 July 1943: Cayo Confites, 270 nautical miles east-southeast of Havana

Pilar lay at anchor in the lee of Cayo Confites, about 300 feet from shore. A bored Cuban coast guardsman had rowed Hemingway and his captain, Gregorio Fuentes, out from the island. “Just fire a shot, when you want a ride back in, caballeros,” he said.

The two men watched the small boat return to shore and scanned the beach to where the where the rest of the Pilar crew sat around a crude table beneath a palm-thatch roof, five men drinking and playing poker. The men on Pilar spoke in Spanish. Fuentes, a Canary islander by birth and boatman to his very core, spoke first.

“The new man is fitting in well. He knows nothing of the sea, but he learns quickly. Besides shooting, he is also skilled at cards and devours my ceviche. I just made a new batch from that picua we caught yesterday.”

“Coño, Gregorio! Do not feed the men barracuda, especially our Polack. You are going to infect them with the cigua sickness. In the Bahamas, I saw strong men fall to the ground from barracuda, made useless.”

“Do not concern yourself, Don Ernesto. First I fed the liver of the fish to one of the beach cats, and he swallowed the meat without hesitation. This is how we know that the fish is free from the cigua poison.”

“Sounds like hoodoo-horseshit to me, Gregorio, but never mind. Let us talk about this new mission. We leave day after tomorrow for Nassau. Same cover: We are researching pelagic species, maybe we should add a cigua study to our story.”

“Clearly then we are going to Nuevitas tomorrow to refuel,” Fuentes said. “We have less than 100 gallons.”

“Correct. Then we ride the tide out of Nuevitas at dusk, and cross the Old Bahama Channel as slowly as possible. Trolling speed. Even so, we will arrive in the dark, so we will anchor at the edge of the banks and snooze until sunrise. Then with the morning light to starboard, we will cross the banks to the Tongue of the Ocean. Deep blue waters. Not just deep, but deep enough to hide a pack of Nazi U-boats…

“And that is the story we will tell the men: Same mission, different place. A lie inside a lie. But not for you, my friend. This time we are not hunting submarines, and you shall have the truth; too much truth, I fear. And you must never tell anyone.”

“You may put your trust in me, Don Ernesto,” Fuentes said.

“I know you have been wondering about Bonkowski,” Hemingway said. “Like Sargento Don, our radioman, he is a soldier but a different type. The Ingleses have trained him as an assassin, and we have been ordered to carry him to Nassau to kill a very important man, and get him out again.”

“Who is this man, and why must he be killed?” Fuentes asked, and Hemingway told him what he knew of Harry Oakes and the pro-Nazi cabal with whom the Duke of Windsor was associated.

“But it seems this Oakes is no more a criminal than the many fascistas that we have today in Havana, always talking big talk about how they will take control once Germany wins the war.”

“The man must die because the British need to control another man that they dare not kill, that royal parasite…but I repeat myself,” Hemingway said. “Yes, you are correct, Gregorio. Killing Oakes will be a crime, but a small one in the scheme of things. War, no matter how necessary or justified, is just one big, fucked up, non-stop crime.”

“Then the question is why us, Don Ernesto? You are an American.”

“Because I screwed up, Gregorio. And the British are a devious people, made more devious by a war for survival. My conversation with the British naval officer was surreal, like those paintings you do not much like.”

“A woman should look like a woman, and a fish, like a fish,” Fuentes said. He’d said it before.

“Nothing is how it seems. They threatened me, Gregorio, because they found out that I had once agreed to help the Russians gather information. Washington doesn’t know it, and if J. Edgar Hoover were to find out, it could hurt me bad.”

“The chief of your national police who is a maricon?” Fuentes asked, “a faggot?”

“I must have been a little tight when I told you that, but yes that’s the man, and he wants to hurt me. First the naval officer tells me that Hoover was queer and suggested I could use it to blackmail him, then a few minutes later, he was threatening to tell Hoover about me and my Russian connection. Surreal.”

“How can a man like Hoover be a leader of police?” Fuentes asked. “The church says homosexuality is a sin, an abomination.”

Hemingway smiled. “You know how I feel about the church. Yes, sometimes when I think about what those people do, I am disgusted, but during the First War, when I was driving the ambulance, I knew the maricones among us on the medical staff. There were more than a few. They did their work with great courage under fire and with great compassion. After seeing that, I cannot despise them all.

“Cago en la leche,” Gregorio, “I shit in the milk of Hoover’s mother, but not because he is queer. I shit in her milk because Edgar Hoover would be just as happy as the head of the Nazi Gestapo. And now we must deliver an assassin to Nassau because I cannot go to Washington and shoot that other son of a whore myself.”

18 June 1943: Cap-Haïtien, Haiti

Odelin Duvalier and the Haitian sailors wrestled sacks of charcoal onto the deck and into the hold of a 44-foot sloop lashed up against a crumbling quay. He remembered being assailed by the smoky smell just a month ago as he clambered onto the deck of the submarine; it was his first impression of the country. He wondered whether some of the sacks contained that very stuff—his memory in a bag.

Albert Pierre was the boat’s master, the son of a son of a Haitian trader. His grandfather, also Albert, had proudly told him that the Pierre family had been engaged in the Bahamas trade since 1804. In all the intervening years, the boats’ rig had barely changed, a design granpapa said had come from a place called Britany in France hundreds of years before.

Pierre stood aside as the men labored and counted sacks as they were stowed. The aft hold was full of pineapples; lashed on deck were two dozen charcoal stoves, tinkered from all manner of dissimilar sheet metal. A good cargo, he thought, but his prime export was the man, Odelin. When the German trader told him how much gold he would receive upon the safe return of this fellow, he had offered to sail the messenger to Nassau with an empty hold, but the trader said no, insisting that the voyage should have all the appearance of a normal run.

Coughing, he corrected a young boy in the crew. “Hey, stupid ass, not that way, the other way. If all the sacks are stacked in the same direction, they may break open as the boat pounds in the waves. Criss-cross each layer like the others are doing. Yes, that a boy.”

Pierre was 43, nearly as old as his grandfather when he died. His cough came from years of inhaling the dust from the charcoal his boats delivered to the islands in the north. The voyage they were about to embark upon was a chance for him to cash in, maybe hire one of his cousins to do the captaining and relax in his old age.

Pierre’s plan was not really a plan at all; it was a habit. They would ride the summer trade winds keeping Great Inagua, an island of salt and pink birds, to starboard and passing in darkness. Using the small compass mounted in a wooden box by day and the North Star by night, they would set a course northwestward, to sail in the lee of the islands and archipelagoes of the southeastern Bahamas, following the wake of his ancestors to Nassau town. They would stop at the Bahamian settlements along the way to sell charcoal and stoves, while keeping the pineapples and sacks of ginger root secreted until Nassau where they would fetch a higher price.

The German had specified that Odelin Duvalier was to be taught the rudiments of the Creole language since the nuns that supposedly had taken him from Haiti as an infant had neglected this part of his education and raised the orphan entirely in French. Aside from the color of his skin, Duvalier did not look particularly Haitian, and, privately, Pierre had his doubts about his story, but he cared not. He encouraged his men to interact with this mysterious messenger, which proved no problem whatsoever once they learned that he had been raised in Africa.

“Tell us again, brother. Does the elephant or the lion win in a fight?” “Is it true the Giraffe has eyes like a person and antennas like a bug?” “Will a horse fuck a zebra and will God give them offspring if they do?”

Duvalier, who could have talked all day about camels, did not have the heart to tell them he had never seen a lion, an elephant or a zebra. Nonetheless, he answered their childlike questions in French and broken Creole, applying his imagination to the photographs and drawings he had seen in books and magazines. And he had a little fun with them, as one does, answering children’s questions. “If a white horse fucks a zebra, the offspring wear spots like your dominos. If the horse is black, the pattern is reversed.”

The skipper’s laugh turned into another round of coughing. Pierre considered himself well educated for a boatman, and he appreciated good bullshit when he heard it. Just how does it happen, he asked himself, that we live here in Haiti by day, and have done so for centuries, but at night crazy dreams still carry us back over the sea to Mother Africa?

Next: Hemingway navigates Pilar across the Great Bahama Bank. Sipriz sails safely past Horseshoe Reef. Meanwhile, “Bay Street Boys” plot to bring casino gambling to Nassau.