Q&A: Expert Dispells Ciguatera B.S.

Most of the Stuff You Read on Facebook About Toxic Fish Is Wrong

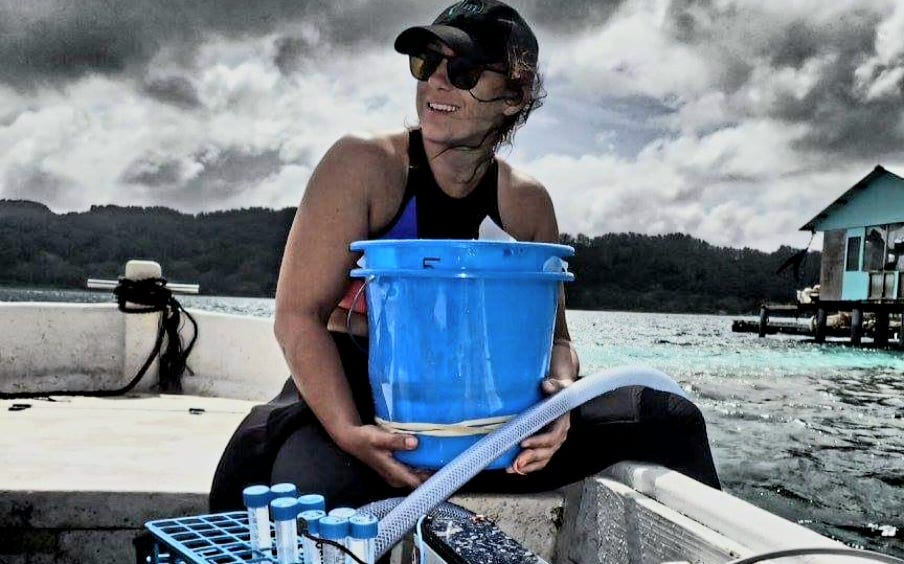

After a spate of posts on Facebook showing astonishing ignorance about the dangers of eating barracuda in the Bahamas, Loose Cannon contacted Clémence Gatti, who has a PhD in Pathophysiology and works as a researcher at the Laboratory of Marine Biotoxins at Papeete, French Polynesia. She is one of the world’s foremost experts on ciguatera.

Loose Cannon: How did you become a leading authority on ciguatera?

Clémence Gatti: Our laboratory has been specifically created to study ciguatera more than 50 years ago. Therefore, we benefit from a considerable insight and experience on the issue. Additionally, we are the only laboratory in the world with a team entirely dedicated to this subject, approaching it from various angles. Our team comprises specialists in ciguatera-causing microalgae, toxin chemistry, detection tests, epidemiology of the disease, and ciguatera environmental monitoring. We are a small team and work a lot through international collaborations to address potential gaps in other expertises or technical facilities.

L.C.: Just what is ciguatera?

Gatti: Ciguatera is a foodborne illness due to the consumption of fish or marine invertebrates from tropical and subtropical reefs, contaminated by neurotoxins (the ciguatoxins, CTXs) produced by a microalgae, called Gambierdiscus.

L.C.: One Bahamian man told he experienced simultaneous paralysis and uncontrollable diarrhea after eating a barracuda. Is that typical? What else can happen if you eat a ciguatera fish?

Gatti: Transient paralysis is not common but can happen in severe cases. Ciguatera poisoning is characterized by a wide diversity of symptoms: digestive, neurological, cardiovascular, rheumatological and multiple general symptoms, with some characteristic signs such as intense itching, cold allodynia (pain in contact with cold objects or liquids), tingling of extremities and around the mouth. One other specificity is that symptoms can be reactivated by the consumption of marine products, animal proteins, alcohol, peanuts, etc. This "hypereactivity" to food and drink can last for weeks, months or even years after the poisoning. More than 175 signs have been reported in the literature.

L.C.: In discussions about eating barracuda on social media, a variety of prescriptions have been advanced for testing whether that species is fit for consumption and, in some cases, ways to mitigate any toxins. I have collected some folklore, mostly from the Bahamas and the Caribbean.

Gatti: In the Pacific as well, numerous folk techniques are employed to try to identify toxic fish and limit exposure to toxins. We share some common practices with those you mentioned. Additionally, we have conducted laboratory comparison tests with some of them to verify their accuracy.

L.C.: For example, hang the body up by the tail, and allow the blood (and any poison?) to drip out.

Gatti: Unfortunately, when a fish is contaminated, the toxins, which are lipophilic, deeply bind in the muscles, viscera, eggs and head. Therefore, draining a fish of its blood does not eliminate all the toxins.

L.C.: Cut out the liver and see if ants will swarm on it.

Gatti: Here too, the population uses the ant or fly test, assuming that these insects have the ability to detect the presence of toxins. This test has no biological basis and unfortunately does not seem to be effective.

L.C.: Cut out the liver and see if a cat will eat it.

Gatti: It is true that dogs and cats are highly sensitive to toxins. They have long been used in laboratories due to their high sensitivity. Some residents of remote islands still use dogs to test their fish. However, these animals do not have the ability to detect the presence of toxins; they will eat the piece whether it is contaminated or not. However, due to their high sensitivity, they will quickly become ill within hours, showing motor and respiratory distresses, and may even die. It is by observing their behavior after consuming the fish that people can get an idea of its toxicity.

L.C.: The poison is in the spinal fluid, so do not steak them.

Gatti: As I mentioned earlier, ciguatoxins, unlike other marine toxins that remain confined to certain parts of the fish, are widely distributed in the flesh, head, viscera of the fish. So, if a fish is contaminated, avoiding the perforation of certain organs will not remove the toxins already bound in the rest of the fish's body. However, it appears that toxins are more concentrated in the head, eggs and viscera. Therefore, avoiding their consumption limits the ingestion of a significant amount of toxins. The liver is indeed a concentrator of toxins, and its consumption is often associated with more severe forms of poisoning. Also, in case of doubt, we recommend avoiding the consumption of these parts. But if the fish is contaminated, toxins will still be present in the flesh.

L.C.: If the teeth are white you can eat it. Red teeth indicate ciguatera.

Gatti: Here as well, fishermen use the "hemorrhagic" test. Fishermen do not specifically look at the teeth but cut near the tail and check for blood clots in the flesh. This phenomenon could be explained by the hemolytic action of another toxin also produced by the microalgae that produces ciguatoxins. We conducted a study on this test about a decade ago. While it is not 100 percent reliable, we observed that experienced fishermen who practiced this test and were familiar with the fishing area had more than a fifty percent chance of identifying a toxic fish. For some of them, we reached a 70 percent success rate, which corresponded to what we had observed when testing the same fish in the laboratory.

L.C.: Eat a really small serving first to test it.

Gatti: The question is more complex. In ciguatera, we observe a phenomenon of “the straw that breaks the camel's back.” The symptoms of the poisoning may only appear when a threshold of toxins in your body is reached, and this threshold is likely variable from a person to another. It is certain that the more you consume a contaminated fish, the more toxins you will ingest and show symptoms. Therefore, yes, in doubt, it is preferable to consume a small quantity. You can eat a small quantity and experience no symptoms due to this threshold phenomenon, and mistakenly think that the fish is safe. But if you, like many Pacific inhabitants, are frequent and heavy consumers of lagoon fish, you have likely already accumulated a certain quantity of toxins in your body without triggering symptoms. Then, it would only take eating a very small piece of fish or a fish with very low among of toxins to be enough to trigger symptoms.

We often observe cases where several people eat the same fish in the same quantities, yet only some of them develop symptoms. This is due to individuals' past habits of consuming lagoon fish and the possibility that they may have already accumulated ciguatoxins in their bodies. We often have cases of persons who eat first a small serving of fish without showing symptoms and eat it again the next day thinking that the fish is safe and then showing the symptoms after the second consumption as the total quantity of toxins ingested during the two days was enough to trigger the symptoms.

L.C.: No longer than your forearm is okay to eat. No bigger than 2 pounds is safe.

Gatti: The analyses of thousands of fish that we have conducted show that size is not significantly proportional to the toxicity of a fish. Small specimens may be just as, or even more toxic than larger ones. I am aware that in many countries, regulations heavily rely on the size of the fish. Consequently, numerous texts prohibit the fishing of fish beyond a certain size. However, this is not a sufficient indicator since ciguatera poisoning can still occur with small individuals.

L.C.: Cloudy eyes are bad. No gel spinal fluid is bad.

Gatti: I do not have information on this subject. Some people here also consider the color of the fish to determine its toxicity. However, we have no idea what these factors actually indicate.

L.C.: A couple of your answers to those questions raised the point of accumulation in the human body. You seemed to be saying that someone, for example, could eat a barracuda that was full of ciguatera one day, but suffer no ill effects because the toxin did not reach critical mass in his or her body. Then they could eat some other fish a week later with a small concentration but enough to reach an accumulation that puts that person over the edge and full blown symptoms ensue?

Gatti: If the fish is highly contaminated, symptoms will appear in all consumers, regardless of their fish consumption habits, and even in a person who has never been exposed to ciguatoxins before. The scenario I was talking about applies to "borderline" fish or that contains small traces of ciguatoxins. In these cases, the history of fish consumption of the consumer and his individual susceptibility may play a significant role in symptoms appearance.

L.C.: Got it. Most of those folklore "tests" came from Americans visiting the Bahamas by boat. What can you tell us about the Bahamas vis a vis ciguatera?

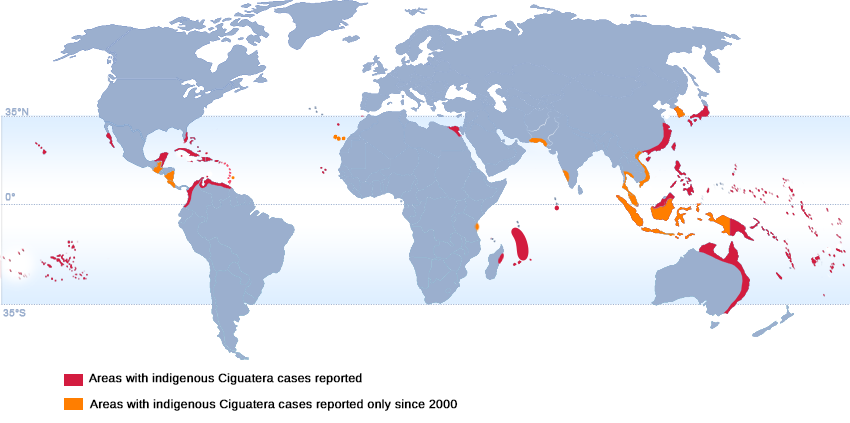

Gatti: It is very challenging to obtain accurate data at global scale, as very few countries have a ciguatera cases reporting system. And in many country who have a reporting system, CP reporting is not always mandatory. This is the case in French Polynesia. We have a ciguatera reporting system associated with a real-time risk map and statistics (if you want to see: ciguawatch-app.ilm.pf) but ciguatera reporting is not mandatory. So, this implies a significant work in raising awareness among doctors and the general population to encourage them to report cases.

Furthermore, the absence of a diagnostic tool complicates the task. Therefore, the limited data we have suffer from significant underreporting.

For your information, I joined a paper that we published in 2021, in which we attempted to compile and compare all available data on ciguatera poisonings worldwide. You will notice that the data is uneven and difficult to compare.

Regarding the Bahamas specifically, the only comprehensive study conducted in the region by our colleagues of the NOAA dates back over 10 years (Tester et al. 2010). At that time, the Bahamas appeared to be among the Caribbean territories most affected.

L.C.: As I mentioned earlier, most of the folklore beliefs about ciguatera we hear about in the U.S. are from the Bahamas. Do you see a relationship between cultures with belief in these cigua avoidance beliefs and a high incidence of people getting sick from it?

Gatti: I am not aware of any studies that measured the impact of these folkloric strategies on the number of poisonings. The fact is that we have to take in consideration another parameter—the risk-taking behavior. Here, we realize that even though the populations of our islands use a lot of folkloric strategies to avoid ciguatera, they are also inclined to significant risk-taking behavior regarding ciguatera. This means that even in doubt, some of them take the risk of eating a toxic fish, advancing the argument that “the pleasure of eating its flesh is stronger than getting sick.”

L.C.: Is there a way we can test whether a fish presents a ciguatera risk?

Gatti: Of course. There are several types of ciguatoxins detection tests. The one we routinely use and is the most sensitive of all, is a functional test that looks for the presence of typical ciguatoxins activity in the fish flesh. It's called the CBA-N2a cytotoxicity bioassay. It allows us to detect toxin traces at the femptogram level (10-15 grams). However, of all the existing techniques (biological or analytical tests), there are no reference methods. The few laboratories worldwide that perform them use different protocols. A significant effort towards standardizing inter-laboratory practices is underway.

As a last resort, I use my husband as a test subject, if I may inject a bit of humor.

L.C.: Okay, so there is no practical way to test the fish we catch?

Gatti: Indeed, there have been attempts in the 90s to commercialize rapid tests, based somewhat on the same principle as a pregnancy test. However, it turned out to be poorly reliable and was eventually withdrawn from the market. The difficulty in developing such a test is that 1. it must be able to detect nearly forty different ciguatoxins, 2. detect traces (micrograms of toxins or less), 3. not have cross-reactions with other compounds and 4. be financially affordable.

To date, only laboratory tests, which require specific equipment, trained technicians, expensive reagents and toxins standards, can do the job.

L.C.: Am I right then to think that people should avoid eating barracuda altogether?

Gatti: Given that marine products become toxic through their diet, any species living in an area with blooms of toxic Gambierdiscus strains is likely to be a vector of ciguatera, whether they are invertebrates, herbivores or carnivores.

However, it is true that in the Caribbean, barracuda frequently appears in reported cases of ciguatera. Its consumption indeed poses a high risk.

However, the following questions arise: Is it because it is more frequently contaminated than other fish, or is it because it is particularly favored by consumers and thus more commonly consumed and therefore more represented in CP records ? I don’t have the answer.

L.C.: After all this back and forth about fish borne toxins, I've got to ask. Do you eat fish?

Gatti: Here's the question!

In French Polynesia, we are fortunate that ciguatera represents, by far, the major risk associated with marine biotoxins. This is not the case in many regions that deal with other harmful algal blooms. However, there are known risks with pufferfish (tetrodotoxins) that I would never dare to eat, and risks associated with the consumption of sea turtles (lyngbyatoxins), which are protected species anyway, and I would never consume them.

Now, considering that I am currently pregnant, I take zero risks with reef fish because of the ciguatera risk, and I do not consume pelagic fish because of methylmercury. It's sad, but I only allow myself to eat imported organic farmed salmon.

The rest of the time, as I manage the epidemiological surveillance network for ciguatera in French Polynesia, I am aware of all reported cases and know the hot spots and problematic species of the moment. This allows me to guide my consumption choices. But most important, I eat small quantities, avoid the head, eggs and viscera, and space out the time between consumption of reef fish. As a last resort, I use my husband as a test subject, if I may inject a bit of humor.

I hate that there is so little to be done to know if a particular fish is affected! Hopefully her work will lead to some sort of an accurate, commercially available test kit in the future. Until then, I guess the gamble method/ risk assessment is the only approach if you want to eat reef fish in the tropics...

The fact that it’s more concentrated In the liver reminds me about the fishing guides in Puerto Adventures, they would lightly taste the raw liver of barracuda, and if it made their mouth and tongue numb, they said it had ciguatera.