Four. Gods and Money

The Haitian sloop must be judged one of the most successful designs in maritime history. Its lines are believed to have been based on the workboats of Normandy or Brittany in France. In the days of 17th century piracy, the buccaneers of Hispaniola would swarm their prey with these nimble craft. For the next 300 years, they worked a trade route from the North Coast of Haiti to Nassau and back.

In the 1970s and ’80s, an estimated 250,000 impoverished Haitians came to Florida, smuggled dozens at a time in boats smaller than 50 feet.

4 July 1943: The Great Bahama Bank

At dawn, Gregorio Fuentes instructed the Basque to raise the anchor as he fired up Pilar’s gasoline motor. Hemingway and the others were off watch and asleep below. Crossing the Old Bahama Channel had been uneventful in ways good and bad. The fish had refused to bite. And now even though there was no hope of hooking a nice Dorado on the shallow banks, Fuentes instructed the Basque to bait the lines and resume trolling.

Fuentes piloted the boat from the flying bridge. Jimmy Bonkowski, his other watchstander, leaned against the pipe rails beside him. Fuentes used his limited English trying to explain the art of piloting by eye, the shades of green and blue that indicated specific depths and the black that meant problemas, as in hitting-a-reef problemas. Trouble is, Fuentes admitted, the sun was too low to discern the colors that would only become more apparent as light came from higher in the sky.

“Pescado!” the Basque shouted, and Fuentes pulled back the throttle to a crawl. “Jimmy, derecho, derecho,” Fuentes said, gesturing straight ahead. Handing the wheel over to Bonkowski, he climbed down into the cockpit. He was certain it was another picua. Barracuda was about all you could expect to catch trolling over the banks. It was indeed, and a feisty one, and it took a few minutes for the Fuentes to finally pull the big fish over Pilar’s transom-wide roller and into the cockpit.

Fuentes, thankful for a cooler restocked with ice at Nuevitas, reached into the tackle box for a fileting knife. “Armando,” he said to the Basque, “take the wheel from Mr. Jimmy and return us to trolling speed. Oh, and bring me that jar full of my ants… Gently, Armando.”

3:15 a.m., 20 June 1943: Somewhere off Horseshoe Reef

First the boy vomited over the side, then Odelin Duvalier. He wished he were dead.

June was normally one of the most settled months to cross from the Greater Antilles to the Bahamian archipelago, but squalls were always possible, and this one, Pierre thought, was the worst he had seen since he was a boy. The wind was howling through the rigging, rain came down in sheets, and the waves had risen to 15 feet in a confused froth. Sipriz, as Pierre’s heavily laden boat was called, pounded and rolled.

But Pierre’s granpapa had saved his life again. The boat’s gaff—the higher of two booms—was shorter and crutched to the mast close to top, very much unlike the traditional Haitian sloop sail plan. The benefit was that in the event of a storm it allowed the crew to shorten sail very quickly just by dropping the peak of the gaff and lashing it.

So it was. With reduced mainsail and the small jib sheeted to the opposite side, Sipriz rode the confused seas as best it could, making slow headway a few points off the wind.

The great Horseshoe Reef should be to starboard, Pierre thought. And their course should be carrying Sipriz away from the unmarked ship-breaker, but in the rain and darkness, he could not use the compass and no stars beckoned. His stomach was tight as a rope with a strain on it. He prayed for an end to the storm.

Andre and Pierre’s two cousins clutched whatever was handy, and they too prayed—out loud, swinging their heads and gesturing with their free hands. To Duvalier, whose kinfolk spoke to God in a more restrained manner, their hysterical voices were an incoherent mix of “ulalulolula” vowel sounds. He wondered whether they were communicating in the language of the voodoo spirits that he had heard about.

Curiousity trumped nausea, and Duvalier shouted the question over creaking and clanking of the boat and its gear. “Capitaine, who are they praying to, some sea demon?”

“To God, you stupid ass. They pray to God.”

The squall subsided as quickly as it had risen, and the constellations blazed through the openings between the clouds. Pierre brought the boat back to a northwesterly course, by putting Polaris off the starboard bow. The men hauled the gaff back into place, and the off-watch crew went below to snooze atop charcoal sacks padded with layers of palm fronds. Unusually for the Trade Wind belt the breeze had nearly disappeared and Sipriz wallowed in the remnants of the chop, barely making way.

By noon the wind had risen and the sky was a mix of clouds and sun. Except for Duvalier and the captain, who had donned spare clothes, the rest were naked, having hung their shirts and trousers on the rigging to dry.

“Mon dieu, capitaine, do you see it? The clouds ahead are green.” Duvalier found this astonishing.

“Maybe I should tell you, as I joke with my boys, that the rain in the Bahamas tastes like mint, but I believe you to be a thinking man, Odelin, so I will refrain from fucking with you.

“We are in deep water here. Deep as hell, but ahead there is a great bank where the water is very shallow, and you can see the bottom and you can see everything that swims or crawls over it. There the water is green, and the clouds reflect the water like a mirror. It is good because it keeps us steering the boat in the right direction. In a couple hours you shall see for yourself.”

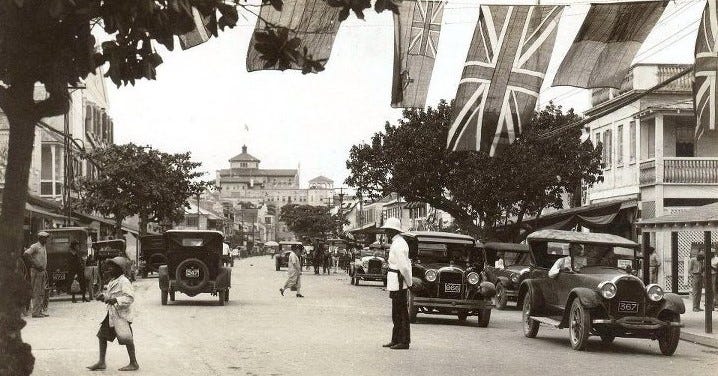

4 July 1943: Christie Real Estate office, Nassau, Bahamas

The “Bay Street Boys” was a clique of bankers, realtors and businessmen who constituted a shadow government over the 700 islands that comprised the Bahamas. Their God-given mission was to divert much of the scant wealth generated in the colony to members of the white minority in general and themselves in particular. Having enticed Harry Oakes into moving his enormous wealth with him to Nassau, Harold Christie had risen from a grasping and not very clever real estate developer to the cock of the Bahamian walk.

Today, though, was not a good day for Christie. The boys had insisted on meeting, and their insistence grated on him. And now the banker was interrupting him—in his own office.

“That’s all fine and good, Harold, but your pal has just withdrawn another million from his account, no doubt headed to Mexico like the last suitcase-full of dollars. If this keeps up, it will be a disaster for all of us. We need that capital.”

“And it gets worse,” said the lawyer. “You know how hard we have all worked to try to bring gambling to New Providence. When were you going to tell us Oakes was working against us? We had the Duke on our side. Now he’s waffling because of Oakes. Oakes is your partner. Why can’t you control him?”

“He’s not my partner, and I have no idea why he’s against the casinos,” Christie said. “He is just a friend who happens to have invested in some of my projects.”

“More like you owe him a lot of money, so now he owns you,” the banker shot back.

Christie tensed. “Same could be said of you.”

“Look, Harold,” the lawyer said. “Mr. Lansky has promised every man in this room 100K just take care of the preliminaries and after that—what did he call it, Stuart?”

“A piece of the action,” the assemblyman said.

The lawyer: “Yes, a piece of the action. So do you want to give the news to our Jew gangster that bets are off, or do you want to make an effort to bring your drinking buddy to heel?”

Christie, thoroughly browbeaten: “Alright, I’ll talk to Harry. I’ll reason with him, but he’s not used to being told what to do.”

“Sooner rather than later,” the banker said. “He’s going to his summer house in Maine next week, and you know it. His wife and family are already up there.”

Next: The crew of Sirpriz act to prevent a child rape, and Hemingway’s steganographic skills disappoint.